The post Welcome appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>Welcome to my personal website. This is largely a holding site with background information about me and my ongoing projects, rather than something frequently updated. More information about those projects can be found on the Inequality and About Me pages. The About Me page also has my contact details in case you want to get in touch. Thanks for visiting.

The post Welcome appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post NZ govt spending above average – OECD appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The New Zealand government spends more than most OECD countries – but with a smaller number of public sector workers than its counterparts, according to the OECD’s Szuzsanna Lonti.

Giving an Institute for Governance and Policy Studies lecture earlier this week, she said general government expenditure as a proportion of GDP was 49% in New Zealand, against an average of 45% across the OECD. New Zealand’s spending had increased notably 2009-11, but “the main explanation would be that by 2011 the spending due to the earthquake started”.

However, compensation for government employees was “below average”, and the number of people employed in government as a percentage of the total labour force was just 9.7%, against an OECD average of 15%. Some countries, such as Norway and Denmark, had levels of around 30%.

Outlining other findings from the OECD’s recently released Government at a Glance programme, Lonti said there were many areas where New Zealand performed better than the average, including:

The proportion of people who have confidence in their national government

New Zealand: 61%

OECD average: 40%

Amount of fiscal consolidation required to get government debt down to 60% of GDP by 2030

New Zealand: 2% of GDP

OECD average: 3% of GDP

Female MPs as a proportion of all MPs

New Zealand: 33%

OECD average: 25%

Time taken to process tax refunds

New Zealand: 28 days

OECD average: 40 days

There were also some areas in which New Zealand performed at around the OECD average, including:

Percentage of citizens using the Internet to interact with public authorities

New Zealand: 50%

OECD average: 50%

And there were some areas in which New Zealand performed below the OECD average, including:

Earnings advantage (net present value) for men of having a tertiary qualification

New Zealand: US$38,000

OECD average: US$105,000

The post NZ govt spending above average – OECD appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post The reality of unemployment appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>It’s sometimes said that people living in poverty just need to try harder, but I’m not sure how much more Amy Scott, profiled today in The Press, could be doing:

Amy Scott and her two children have moved houses five times since the earthquakes. Scott lost her job after work as a bartender “dwindled off”. She lost her mode of transport in a minor accident.

She is now on the benefit, and after paying rent and power, she has $70 a week to spend on food.

“It’s a struggle; each week I have to choose which bill I’m going to pay. It’s really hard, especially when you’re used to earning,” she said.

She had been seeking work since losing her job in July, but was finding it hard to compete with the influx of other candidates for the positions.

“I’ve been to every bar, every retail place, supermarkets, The Warehouse … in the past month I’ve handed out 30 CVs.”

She pulled her daughter from Girl Guides because she could not afford the fees. She could not afford to send either child to relatively inexpensive activities, including swimming lessons.

Once again this makes the point that being in poverty is so often about having constrained choices, not the luxurious range of wonderful free choices that are supposedly on offer.

The post The reality of unemployment appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post Action against exploiting migrants welcome appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>There’s been some good news over the weekend, with the government announcing tougher penalties for people found to be exploiting migrant workers.

There’s been a lot of coverage of this in recent weeks, including stories that workers in Auckland are being paid as little as $4 an hour, or exploited by the firms that bring them in from overseas.

So it’s good to see the government tackling this. A significant part of the story of inequality is that many people work in industries where there are very few protections for them as workers. These moves start to tackle that – as long as they are properly resourced, of course. One of the lessons of Pike River is that it’s hard to protect people and enforce standards if there aren’t enough inspectors to do the work.

The post Action against exploiting migrants welcome appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post Why it IS about poverty: the crucial numbers appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>One of the many things obscured in last night’s The Vote about children’s issues was the simple fact that incomes aren’t high enough at the lowest end for parents to give their children a decent start in life.

The figure of $30,000 being ‘poverty’ for a family with four children was tossed around as if it wasn’t real poverty, but no-one broke down the figures for what it’s like to be on a minimum income.

A two-parent family, even with just two children, living on one full-time minimum wage salary of $540 a week (2012 figures), has around $460 after tax, and maybe $790 with Working for Families and the accommodation supplement.

Rent can easily be $250, feeding a two-child family well – by meeting nutritional guidelines in the cheapest way possible – costs about $260, running a car is around $85. Power costs can often be $50.

So once bare survival is taken care of, just $145 a week may be left for everything else: $5 a day per person to cover clothing, a phone, replacing or repairing appliances, healthcare costs, and so on.

Since that’s obviously not enough, something has to give. And that’s why children come to school without having had breakfast, or proper clothing; that’s why they live in houses that aren’t properly heated.

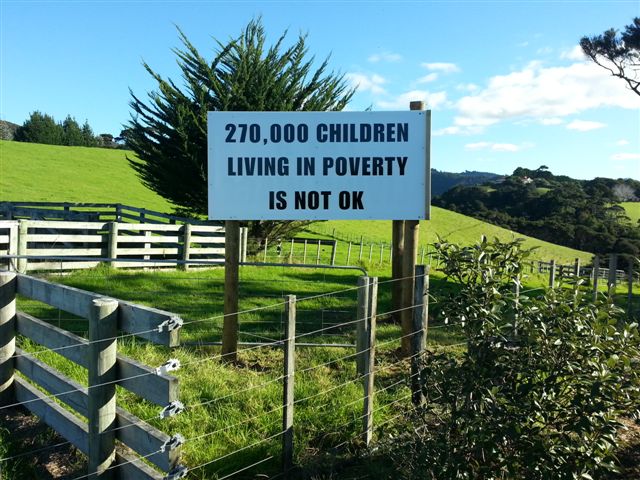

This is why people say there are 270,000 children in poverty: they are the children living in families like the one above, families with less than 60% of the income of an average household in New Zealand.

Not only is that – as Russell Wills pointed out – an internationally standard definition, it’s also the amount that focus groups with real New Zealanders have shown to be the minimum amount to have a vaguely decent life.

So yes, anything under that is poverty.

The post Why it IS about poverty: the crucial numbers appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post Wellington takes huge step towards Living Wage appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>Wellington City Council has just voted to support the Living Wage ‘in principle’, put $250,000 in the budget to research and implement it, and – crucially – has extended it to cover contractors not just in-house staff.

It’s a great moment: not 100% of the way, since they haven’t put aside all the money needed, and there are some more hurdles to clear, but a huge step.

The council voted unanimously to get officers to prepare a report, by November, on the Living Wage and what it would mean – and they could easily have stopped there.

But 10 out of the 15 also voted to support it in principle – even before officers report back – and to put the money aside for it.

The 10 who supported it were: Celia Wade-Brown, Ray Ahipene-Mercer, Stephanie Cook, Paul Eagle, Leonie Gill, Justin Lester, Bryan Pepperell, Helene Ritchie, Iona Pannett, and John Morrison.

Those who didn’t were Ngaire Best, Jo Coughlan, Andy Foster, Simon Marsh, and Ian McKinnon.

It’s worth noting that Morrison supported it, since he’s the principal challenger to Wade-Brown in this year’s mayoral elections, so it bodes well for the Living Wage surviving past October, whoever wins the election.

Of those who opposed it, Ngaire Best is understood not to be running again, although that’s not confirmed.

Paying contractors the Living Wage is a massive step, because it would have been so easy to stop at in-house staff. Shows the principle is getting through.

Also significant that a plan to limit the Living Wage to those with 4000 hours already at WCC was dropped. That would have given other councils a major ‘out’: they could have also taken half-hearted steps. Now the trail is clearly blazed, and one can only hope that others (esp Auckland) will follow suit.

Anyway the bottom line is a big win for equality and fairer pay all round.

The post Wellington takes huge step towards Living Wage appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post A simple message about child poverty appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>I’ve just been sent this image by some good people who have put this sign up in the Waipu area.

Nice and simple … and effective.

The post A simple message about child poverty appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post What the Treasury thinks about inequality appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The Treasury has just released a paper outlining its thoughts on inequality (as part of its wider work on Living Standards). Now, it’s great to see the Treasury acknowledging that it matters how income is distributed – not just how much of it we generate. Unfortunately, it hasn’t quite faced up to the full reality of the problem, which leaves its account very weak, and in places incoherent.

The Treasury says its starting point is “the ability to participate in society”, which is a fabulous place to begin. The whole point about inequality is not just that people need to be lifted above an absolute level; inequality means they are left out of things that other people have, unable to join in with the rest of society, in way that is determined by how much other people have.

Unfortunately, the Treasury doesn’t seem to realise what that really means, because its proposals are then focussed almost entirely around improving social mobility. Now, social mobility is important: people need opportunities to earn more, or to live better than their parents did. But it isn’t enough by itself.

Even if people can move freely up and down the ladder, there is obviously still a ‘down’ – and being in that ‘down’ spot is miserable. To put it differently: even with mobility, there will always be people who are very poor and don’t earn enough to participate in society – even if they are doing useful work. Tamara Baddeley, a woman whose story will be told in the Inequality book, cares for the elderly, is paid $14.81 an hour – and can’t afford to go to the movies. To talk about ‘opportunity’ and mobility’ is meaningless here.

What is needed is direct action to tackle inequality now: action to raise her salary, so that she can participate fully. The Treasury’s view, which seems to be that it doesn’t matter if people are desperately and unfairly poor, as long as it’s not for long, is woefully inadequate – not least because, by its own measure, people need more income – right here, right now, whatever they are doing – if they are going to be able to participate in society (like being able to go to the movies).

In addition, the Treasury seems to have missed the obvious point that if you want to increase social mobility and offer equal opportunities to all, you need greater equality of incomes. To state the obvious, if some people have far more wealth than others, their children will get a much better start in life. In addition, some whole communities become cut off from opportunity because, when poverty is concentrated, there are few jobs going, their communities aren’t adequately invested in, and they become characterised by hopelessness and despair.

The international evidence is that, across countries, more equal societies have better mobility (far more people make it out of poverty in Denmark than they do in the US), and that, across time, as inequality increases, mobility decreases. The US shows this: as gaps have widened, people’s ability to escape poverty has fallen. Again, the Treasury’s paper fails to take into account this basic point.

Another problem with the paper is that it gives an extremely biased account of why inequality has risen in New Zealand, discussing technological change and different household patterns, but not mentioning little things like lower taxes on the very wealthy and reduced benefits for the poorest. Nor does it mention the decline in union membership, which some overseas research suggests is responsible for up to one-third of rising inequality. The failure to even mention this factor is just staggering.

Still, it’s good to see the Treasury engaging with the issue. As with The Economist’s (similarly partial) special feature on inequality last year, the fact that the issue can’t be ignored now is a huge positive in itself.

The post What the Treasury thinks about inequality appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post The wonderful world of Wellington’s magazines appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>Vicious reviews of amateur singers, ambushing Robert Muldoon and interviewing gnome collectors … Wellington magazines have done all this, and more, over the years.

“This magazine … is made to sell.” Such was the philosophy of the flamboyant Charles Nalder Baeyertz, editor of the literary, musical and cultural magazine the Triad, which he ran from a villa in Mt Victoria after moving north from Dunedin in 1909. And sell it did, thanks in part to Baeyertz’s notorious frankness as a critic. He once described a sermon as “adding nothing new to our ignorance of God”, while one set of poems submitted to the magazine was returned with the note, “Publish it? No! Poison yourself first; you’ll be glad of it after.”

Despite expanding into the Australian market in 1915, the Triad eventually collapsed in the late 1920s under the weight of misdemeanours by drunken writers, the difficulty of trying to appeal to audiences on both sides of the Tasman, and lawsuits from offended tenors. (The magazine managed to survive one lawsuit after it described a singer as having a voice like “a pig’s whistle”, but lost heavily when it compared another to “a trussed turkey”.)

Read the full article here: FishHead – Wellington magazines history – July 2012

The post The wonderful world of Wellington’s magazines appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post Nice to Meetup … to Meetup Nice appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>Thousands of Wellingtonians use Meetup.com to make new friends, explore hobbies, and even build new communities. So what’s the deal with the site – and is it for you?

When Scott Heiferman built a website to help his New York neighbours come together in the wake of 9/11, he expected a number of things to come from it. But not, one imagines, a zombie flash mob. Still, that’s what he got, thanks to the enthusiastic embrace of his site Meetup.com by the thousands of Wellingtonians who use it on a weekly basis.

Heiferman had been a tech entrepreneur with a string of successful businesses behind him – including the online ad agency itraffic – when those planes crashed into the twin towers. In the aftermath of the disaster, he was struck by the way people connected with each other. “For a little bit there, New York became a pretty friendly place,” he told a conference several years ago. “I talked to more neighbours in the days after 9/11 than I had in recent years of living in New York, having moved to New York from Iowa, a few years earlier.” The result is a global phenomenon that has drawn in over 11 million people in 45,000 cities.

Read the full article here: FishHead – Meetup.com – January 2013

The post Nice to Meetup … to Meetup Nice appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post It’s a nice day for a penalty spot wedding appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>What would marriage ceremonies look like if men had their way?

Most weddings, when it comes down to it, are pretty much the same. The bride wears white, or maybe cream. The groom wears a suit, uncomfortably, and gives the impression that it’s the first time in his life he’s met this novel form of attire. The groomsmen follow suit (pun intended).

The ceremony itself features readings of either the passage from Corinthians (“Love is patient, love is kind”), The Prophet (“Let love be a moving sea, etc, etc”), Shakespeare (“Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments”), or, in some cases, all three. Then you get the same speeches, the same meal, and more or less the same music afterwards.

This sameness arises, I feel, from two factors: the need to satisfy a wide range of views, among parents, friends and wedding organisers, as to what makes for a good marriage; and the way in which the ideal of the perfect marriage, and all its traditional trappings, is drummed into every young girl from an early age.

Read the rest of the article here: FishHead – Weddings – September 2012

The post It’s a nice day for a penalty spot wedding appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post The truth about Wellington’s food markets appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>Wellingtonians love their weekend food markets – but do they realise that much of their fruit and veg comes not from the stallholders’ own soil but from a warehouse in Johnsonville?

It’s a clear, sharp-edged morning at Harbourside Market, where, in the shadow of Te Papa, the fruit and veg stallholders are doing a brisk trade in cauliflowers, capsicums, oranges and broccoli. This is, supposedly, one of the more intimate ways to buy food: outdoors, away from the sterile air of the supermarket, and with a vendor who has some kind of personal connection with their wares.

And yet, at Harbourside, as little as one piece of fruit in five will have been grown by the person selling it; the rest is bought midweek from the wholesalers in Grenada North – and that food can come from anywhere in the country, or indeed the world. Not that there’s necessarily anything wrong with that. But it does raise the question of just what we think we’re getting when we reach our hand into that basket of broccoli.

Read the rest of the article here: FishHead – The truth about food markets – Nov 2012

The post The truth about Wellington’s food markets appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post In shadows, and behind closed doors appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>Walking unseen among us are thousands of homeless, mentally ill and otherwise vulnerable people – many of whom will never get the help they need.

(First published in FishHead magazine, August 2012)On a cold, flat winter’s day, just before dawn, the doors of the night shelter on Taranaki Street spring open, propelling their guests out onto the streets. And so, at 7.30am each morning, begins what these homeless people know as ‘the circuit’.

Their first stop is the soup kitchen on upper Tory Street, where bread and soup are served from 8am. Then the day passes in visiting the Central Library, especially the second floor, which stocks the newspapers; sleeping and hanging out at Courtenay’s drop-in centre, just down from the Majestic Centre on Willis Street; or simply wandering the streets, begging and otherwise killing time. At 4.45pm the soup kitchen starts serving dinner; then it’s back to the night shelter before it closes at 9pm.

And the next day it begins again.

When you work, as I do, at the soup kitchen, this world comes into sharper focus, and it’s easy to think then that you know something about homelessness. But when you probe more deeply, you realise that, paradoxically, those following the circuit are far more visible than the thousands of ‘hidden’ homeless and other vulnerable souls: the people who are not at the night shelter, nor sleeping rough, nor in the care of the state, but who have nowhere permanent they could call a home and receive little help with their many problems. These are the people living in boarding houses – cramped, dirty, often dangerous places that are almost entirely unregulated and charge up to $270 a week for board and food; the people living in terrible overcrowding, sometimes two or three families to a house; the people sleeping in cars, garages and abandoned flats; the people suffering mental health problems supposedly too minor to attract state aid; the people couch-surfing or staying with friends. Behind closed doors, in short, there lies a world of problems.

This sort of homelessness is not the same as the street kind, but it does overlap. Many people on the streets have come from these living situations; many return there. People cycle from couch-surfing to the night shelter to squatting, and back. Both worlds are precarious and unstable, full of lives that have little leeway to cope with sudden shocks.

Not everything, of course, in these two worlds is grim. Many of these people are eventually helped to get the housing and support they need, or they help themselves. Nor are the authorities totally blind to the problem; in fact, Wellington City Council has recently renewed its drive to reduce homelessness and its associated ills. But the problems are many: affordable housing is chronically undersupplied, financial woes are forcing ever more families into desperate measures – and, just when people need more support, some government agencies are withdrawing the hand held out in aid.

***

Though we have not traditionally had reliable figures on vulnerability, statistics to be published later this year will show that in the 2006 census, several thousand people in Wellington were ‘severely housing deprived’, a term that covers both the worlds outlined above. (Given the current economic climate, that figure will only have risen.) Within that, the consensus is that there are 30 or so rough sleepers – people actually living on the streets – at any one time; more broadly, Wellington City Council says the city has 200 ‘homeless’ people, on a narrow definition, up from 160 a year ago.

For a few thousands of people, there are dozens of reasons why they end up where they are – and it is precisely the combination of things, the piling on of many burdens, that does the damage, as can be seen at the extreme end of homelessness. On the day I went to talk to Mike Leon, who has run the night shelter for the last 17 years, he showed me a list detailing the 22 new visitors to the shelter in April. Some had felt unsafe in their previous home; others had been kicked out by family and partners; yet others had been released from jail with nowhere to go. Although a lack of money always hovers in the background, Leon said relationship breakdowns were the greatest problem. People who have few reliable friends and no family ties – which in our atomised world is increasingly common – don’t always have somewhere else to stay when they are kicked out. Even then, one problem is often manageable. But when there are multiple problems, as when someone’s relationship breaks down and alcoholism consumes all their money, or when they have diabetes and a criminal record that makes getting work nigh-on impossible – and then those problems are exacerbated by a sudden shock, like being evicted – it’s then that people fall into the world of homelessness.

One particular problem, of course, is the lack of affordable housing in Wellington: many people are simply unable to afford a place to stay. Beneficiaries who can’t get into a council or Housing New Zealand home have no chance of paying market rents, not when a bottom-end Aro Valley flat can easily cost $150 a week, and the dole plus the accommodation supplement is $300 a week at best. (Internationally, it’s accepted that no one should pay more than 30 percent of their income in rent.) There’s more on offer in, say, Wainuiomata, but that’s little comfort if you can’t afford the bus fares every day. Even a flat in Northland for $100 a week can be unaffordable when transport costs are included. A couple on one minimum wage salary, meanwhile, would be paying half their weekly $500 income on rent if they wanted to live in a bottom-end Aro house.

It doesn’t help that beneficiaries in particular don’t always get the support they deserve. On another day I visited Graham Howell, who runs a benefits advocacy service in Newtown, and he showed me an internal Ministry of Social Development document revealing that only half of all beneficiaries eligible for emergency grants actually get them, because Work and Income (WINZ) staff don’t always inform people of their entitlements.

Duncan, a 30-year-old homeless man who had been in Wellington for two weeks when I met him, told a similar story. He was trying to get on a Salvation Army course to combat his alcoholism, which had lost him his job as a DOC ranger in the South Island, but he had no money left for accommodation or food. The first time he went to see WINZ, the case manager said they could do little to help him while he waited for his benefit stand-down period to end. But when he went back a second time, hungry and desperate, a friendlier case manager helped him get an emergency grant and a food voucher – both of which he’d been entitled to all along.

Of course, in the current climate, WINZ workers have troubles of their own. One Wellington region staff member, speaking anonymously, described to me a culture of staff cuts, constant restructuring and severe stress. Six staff members had left in the last 18 months and not been replaced, and his colleagues often couldn’t take time off because no one could cover for them. Meanwhile, staff were abused on a daily basis because beneficiaries couldn’t get appointments. This, he said, was serious trouble on the frontline.

None of which is to say that the vulnerable people themselves are blameless in all this. Many of their wounds are self-inflicted, to an extent. But Philippa Meachen, who runs the soup kitchen, reflected a widely held view when she told me that the more she sees of homeless people, the more she respects them. Many have had violent or abusive childhoods, or mental health problems, or other things that make them not very employable; yet they keep trying to find work. We may think of ourselves as very different from these vulnerable people, but were it not for a few things, as one soup kitchen volunteer put it, we could easily be on the other side of that kitchen counter.

There are, of course, many different kinds of homelessness. The 22 men on Mike Leon’s list might have all (bar one) been on a benefit or had no income at all, but nothing much else united them. They were all ages, from teens to 57-year-olds. They had come from all over the country, including Auckland, Palmerston North and Foxton, and from different living arrangements – rough sleeping, often, but also boarding houses and living with friends. Many were only temporarily homeless. Though 20 new people turn up at the shelter each month, some do eventually move into permanent housing; others just drop off the radar. The Downtown Community Ministry (DCM) deals with 180-plus people each quarter who are homeless, but not all of them remain so. A very few people sleep rough for decades, but most shuffle in and out of different homes, never quite finding a place to rest.

***

It would be nice to think that, in an economic slump, central government was doing more to help people struggling to cope. After all, the need is there. The number of food parcels being handed out nationwide has doubled since 2008. The Wellington City Mission alone helped 4000 people last year, many of them from working families no longer able to make ends meet. Yet a couple of crucial government agencies are, if anything, cutting back on the services they provide.

The first is Housing New Zealand, which, even though it is the agency that owns and runs most of the country’s social housing, no longer believes it has a social mandate, and has handed social housing policy over to the Department of Building and Housing. Staff who visit tenants in their homes have been instructed to stop helping them with the wider social problems they encounter, and to refer them instead to other government departments. When I questioned them about the move last year, Housing New Zealand was unable to say how the referral system would work or how it would be funded. (The agency refused an interview request for this article.) Housing New Zealand also rejected requests to send a staff member to Wellington City Council’s homelessness forum in June. Elsewhere, the agency has tightened its eligibility criteria: women suffering from domestic violence, for example, are no longer automatically accepted for emergency housing. A shift from staffed offices to call centres has seen people seeking help put on hold for 45 minutes or an hour. And the agency no longer puts lower priority applicants on its waiting list, thus removing thousands of people from the statistics.

The other agency is the Capital Coast District Health Board (DHB), which runs the area’s mental health services. The board has been in the news recently for cutting $270,000 from the budget of the Newtown Union, an organisation that provides healthcare – and in particular outreach clinics for people who wouldn’t normally visit a doctor – to some of Wellington’s poorest families. The board has also cut funding to groups working with refugees and other services as it struggles with a budget deficit caused by the new Wellington hospital and health funding not keeping up with inflation.

But in addition to these well-publicised cuts, the DHB has also slashed mental health budgets and is planning further changes that many fear will spell yet more cuts. They currently fund around 190 ‘supported’ beds, which provide supervised housing for people with mental health problems, but are believed to want to reduce that to 100 as they encourage more patients to rent their own homes and call on services only when they need them. (The DHB also refused to be interviewed for this article.) No one working in this field objects to the overall aim, which is part of the long journey away from locking people up in institutions towards independence in their own home. But the health board is, according to NGOs in the sector, refusing to guarantee that all the funding for supported housing will be transferred to the so-called ‘wrap-around’ services under the new model. The suspicion, inevitably, is that the policy change will be used to drive down the cost of the contracted support services, and the savings used to reduce the health board’s deficit.

One mental health NGO, Wellink, has already had its $8 million budget cut by one-third in the last two years. And it’s not as if funding was generous to start with. Wellink’s chief executive, Shaun McNeil, told me that Wellington – and New Zealand – services have always concentrated on the 3 percent of the population with the most severe mental illness: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and so on. Countless people with lower-level disorders receive no treatment. At a conference in June on post-prison reintegration there were heartbreaking stories of NGOs trying to work with ex-inmates who were self-harming and attempting suicide, or intellectually disabled, or – in one awful case – terrorising their own mother so badly that she fled town. Yet none of these obviously disturbed people fitted the mental health criteria, so the health board teams turned them away. (The lack of support for ex-prisoners is a story all of its own. The Prisoners’ Aid and Rehabilitation Trust (PART), a group funded to help ex-inmates, has only enough money to devote one day – eight hours – to each person released from prison in Wellington. Another problem: many inmates come out of prison with no photo ID, so they can’t set up a bank account – and no bank account means no benefit, which means no income and, often, a return to crime; and so the cycle resumes.)

Wellington City Council’s forum in June canvassed a range of ideas to help tackle or even eliminate homelessness, many of which are outlined opposite (see box). But there are obstacles even at the highest levels. New Zealand has no national strategy to coordinate action on homelessness, for example. And at the local level, the city council – unlike, say, British local authorities – has no legal duty to house the homeless. That means there’s no coordinated assessment, sifting or categorising of homeless people, and no shared central register, as well as few emergency housing options.

Action can still be taken, of course, and the council is particularly keen to break the daily ‘circuit’. Not only is it dull and monotonous, but it maintains rather than lifts people out of homelessness. The council has offered to fund a review of how the night shelter could offer government services onsite, provide more activities for its guests, and move more people into permanent housing. Of course, the shelter might have done all this already, but for a lack of funds. However, a more holistic public service approach could see the Department of Corrections, for example, funding the shelter to provide support for ex-inmates. Similarly, there are questions over whether the drop-in centres – such as Courtenay’s, and Catacombs on Manners Street – could do more to help people out of homelessness. The Downtown Community Ministry’s Lukes Lane headquarters, meanwhile, could be turned into a central ‘hub’, housing all the services that homeless people need under one roof.

But perhaps the single biggest obstacle to ending homelessness – and to helping the legions of people in severe housing need – is the lack of affordable and alternative housing. There is, of course, some already: the city council has 2350 houses, where rents are set at 70 percent of the market price, while Housing New Zealand provides just under 1900, with rents at 25 percent of an individual’s income. (Another 100 or so houses are in the hands of NGOs such as the Wellington Housing Trust.) Nonetheless, over a thousand people are on housing waiting lists in the Wellington region. Both the council and Housing New Zealand have got rid of a third of their stock since the mid-1980s, according to the Wellington Housing Trust. And even though the capital’s population is expected to grow by 55,000 in the next few decades, neither organisation has any plans to build a meaningful number of houses.

Even if there are affordable flats around, many homeless people – and the agencies that work with them – report covert discrimination: landlords will find ways to avoid giving flats to beneficiaries or homeless people. And in truth, some chronically homeless people are incapable of living alone, and would be a trial to any ordinary landlord. What they need is supported housing, which, as mentioned above, Wellington already provides for people with mental health problems. As DCM’s Stephanie McIntyre is forever pointing out, Wellington has a very narrow range of options. Even a wet house for supervised alcoholics seems to be too difficult.

Still, the measures that came out of the June forum, if taken together, would represent a major advance: a real chance to end, rather than manage, homelessness and its associated ills. Because although Ben Hana became a kind of folk hero – to his own and others’ detriment, many would argue – most street living is not romantic. Recently I met one streetie – to use his term – who steered clear of his fellow rough sleepers. Underneath any kindness, he found, was an ulterior motive: someone who offered cigarettes one day would want twice as many back on the next. Many rough sleepers sleep alone, because it’s not always safe to trust the others. Some streeties will stand over others for protection money, or attack them; steel-capped boots are often the weapon of choice.

But then the general public isn’t above a bit of abuse. Mike Leon told me he knew of several cases of members of the public attacking or abusing homeless people. In one deeply disturbing night-time incident, three young women, drunk and dressed up for a night on the town, urinated and defecated on a comatose homeless man lying on the ground just outside the night shelter.

Yet not all is ill; there is kindness, too, and solidarity. One evening I stopped in at the Catacombs drop-in centre, above the Cosmic Store on Manners Street, which is a high-ceilinged, run-down old set of three rooms with a TV and some other basic facilities. It wasn’t very cheerful, but the people there were getting along peaceably enough. One of them, who even had a house of his own, said he came there largely for the company. So, too, did a man who, I discovered, lives in a garage in the Aro Valley, having previously stayed in an abandoned building and in the service area of a multi-storey car park. He’d once had a flat out in Northland, but couldn’t afford the bus fare into town, he said, and no one came to visit, so, rather than die of loneliness, he gave it up. Now he has a door he can shut behind him, a candle, some matches, a sleeping bag, a duvet, and a roof over his head; and this is happiness of a kind.

That same night, I was walking home along Tory Street by the Harvey Norman store when I sensed as much as saw ahead of me the familiar tread of a soup kitchen guest. He was moving with the slow, halting gait of those who have nowhere particular to go, a tread so very different from the hurried, purposeful step of people with places to be and deadlines to meet. I watched this man – 40ish, heavyset, limping – walk haltingly across Tory Street towards Restaurant 88, where a party of young women stood outside, prattling under the neon lights; then he pushed past them into the darkness of Ebor Street. As it was on my way home, I followed him along that road, round its bend and onto Vivian Street. Then he turned into a car park between two buildings and, looking for a place to rest that night, was lost in shadow.

Those following the circuit are among Wellington’s most vulnerable people, individuals who not only lack a place to live but are also often battling drug and alcohol addictions, poor physical health and low-level – or indeed severe – mental health problems. And yet they are curiously hard to see.

Though their circuit may have all the hallmarks of the middle-class daily commute, with its early rising, routine journeys and nightly return, the two patterns of living are like a pair of rings that fit through each other but never touch. Though we may pass sightlessly by one another, almost close enough to touch, luck – or individual effort, depending on your point of view – keeps the two sets of lives apart. And so the most vulnerable people, except the semi-legendary figures like Ben Hana, have a strange kind of invisibility, hidden in plain sight, living literally and metaphorically in shadow.

The post In shadows, and behind closed doors appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post Does Wellington need to be a supercity? appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>Wellington is under increasing pressure to import Auckland’s supercity model. So is amalgamation really the answer to all our problems?

(First published in FishHead magazine, April 2012)

The area’s local councils say there’s no need for such sweeping changes: a gradual process of sharing more services will do the trick, they say. But others claim that the councils’ scattered responsibilities and dysfunctional relationships are stopping the region from being well run, and exacerbating our weaknesses compared to Auckland.

Read the article here: FishHead – Case for Wellington supercity – April 2012

The post Does Wellington need to be a supercity? appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post The threat of inequality appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>I’ve just written a piece for an international project aimed at improving governance – the way countries are run – known as the Sustainable Governance Indicators.

The piece is about our rising inequality, and how it threatens some of the things we hold dear: a relatively free and transparent political system, for example.

It’s here: http://news.sgi-network.org/

http://www.

The post The threat of inequality appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post Why education may be over-rated appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>A recent paper from Britain’s Fiscal Studies journal has some sobering reading for people who think that education alone can solve the problem of how to create more opportunities and greater social mobility for all.

Looking at the UK’s massive rise in the number of people getting degrees, it points out that most of the extra people doing degrees have come from the top fifth of the population; the number of people with degrees in the bottom fifth only rose from 6% to 9%.

Second, the study shows that people with degrees have started to earn far, far more than non-qualified people in recent decades.

“Putting these two together (more education for people from richer backgrounds and an increase in the pay-off to this education) implies increasing within-generation inequality. By reinforcing already existing inequalities from the previous generation, this has hindered social mobility.”

Now, this story isn’t exactly the same in New Zealand, where the earnings gap between qualified and non-qualified people is extremely low by world standards. But the wealthiest have benefited most from the expansion of tertiary education, here as elsewhere.

This doesn’t mean that expansion was a bad idea; in fact, it was probably essential. But, as with many things, it has been badly handled; and – unsurprisingly – this investment in opportunity has failed to help many of the families it was designed to assist. We have instead a self-reinforcing educational elite, what Colin James calls a privileged group or class, bequeathing their educational advantage to their children.

That’s not to say that education is never a vehicle for opportunity and mobility. Of course it sometimes is. But only if you do it right – and just increasing the number of university places is not doing it right.

The post Why education may be over-rated appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post Debating inequality at Te Papa appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>As part of my book on inequality in New Zealand, I’ve set up a couple of Thursday night talks at Te Papa. The first one, on Sept 13th, is a free, open-invite event for anyone who’s worried about the increasing gap between rich and poor in New Zealand. More details below. Another talk in October will look at how to tackle the problem.

Forums for the future: Between Rich and Poor

September 13, 2012 Soundings Theatre, Te Papa, 6.30-8pm

New Zealand has had the biggest increase in the gap between rich and poor of any developed country. But what does that mean – and why should we worry about it? Come and hear three top speakers discuss the serious and urgent threat that widening inequality poses to New Zealand personally, socially and economically.

Speakers:

• Stephanie McIntyre, director, Downtown Community Ministry – sharing real-life stories of how inequality affects people’s lives

• Philippa Howden-Chapman, pioneering health researcher – on the evidence linking inequality with poor health, bad housing and other social problems

• Colin James, political columnist – on how to think differently about inequalities and their place in society and the economy

The post Debating inequality at Te Papa appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post Not doing it for the kids appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>A shortage of childcare providers is forcing parents to drive their kids across the city each morning. Fees are soaring, and parents don’t get the information they need to weigh up the options. So what’s going on in early childhood education?

(First published in FishHead magazine, February 2012)

It is, as Melanie Heaphy puts it, quite crazy. “There’s waiting lists for everything – for kindy, for the paid childcare centres … It’s nuts. People are putting their kids on waiting lists as soon as they are pregnant, just about.”

This is not, it’s fair to say, what politicians envisagedwhen they began vastly increasing early childhoodeducation (ECE) funding in 2005. In that time,spending has gone from $410 million to around $1.4billion, and over 1,100 new centres have opened.At the heart of this revolution was a guaranteed free20 hours of childcare for three- and four-year-olds,designed to ease the strain of child-rearing and helpmothers get back to work. But it’s a guarantee that’sworth little when parents can’t get their child into acentre near their home or work.

Nor is it easy to pick the right centre, or meetcosts of $300 or more a week. That’s not to say thatthe system is in crisis: after all, 95% of children getsome form of early childhood education, standardsare rising, and national waiting lists are falling. Butthat’s little comfort for the parents who find the taskof selecting the right centre to be, as one puts it, “acomplete nightmare”.

There are just over 500 early childhood centresunevenly spread across the Wellington region. Perhapssurprisingly, poorer and more rural areas are wellserved:Porirua has one centre for every 760 people,the Wairarapa one per 910. In contrast, WellingtonCity itself has one for every 1060 citizens – a total of187 centres.

But the real problem is that even within Wellington,some suburbs are starved of places (see chart on page41). Analysis of government data shows that whilewealthy or well-established suburbs such as Karoriand Tawa have dozens of centres, and the areas aroundthe central city (Newtown, Thornton) are well-served,others make do with just a handfull of ECE providers.In particular, the fast-growing southern suburbshave all but missed out. Island Bay’s population hit8,250 in the 2006 Census and has kept rising since,as young middle-class couples have flooded the area.“Island Bay and Owhiro Bay and Southgate are likea breeding colony at the moment,” says local Labourcouncillor Paul Eagle.

“You can drive down there [the Island Bay Parade]in the late afternoon or early evening, and there is asort of a 2-5 lane highway going down each side withpeople pushing prams.”

But despite this baby boom, Island Bay has just threeregistered childcare centres, although other informalones exist. Nearby Owhiro Bay has only one centre.Lyall Bay has one for its 2,600 residents; likewise thenextdoor suburbs of Southgate and Houghton Bay.Although other nearby suburbs, such as Kilbirnie, arebetter served, the pressure for places remains.Sharon Mountford-Gibbs, who runs the Owhiro14 leaving a year, [so] obviously the majorityof those children are not going to get intoour centre,” she says. “There’s just notenough centres.”

The result? Parents have to go “wherevertheir kids can get in”, says Heaphy. Nor is itjust the southern suburbs that suffer: she’sheard of shortages in Porirua and elsewhereas well. (One quirk of this situation is that,despite such strong local demand, the IslandBay pre-school that Heaphy helps run includeskids from Hataitai, Mount Victoria and evenLower Hutt.)

Joanne Aitken, an Owhiro Bay parent whowas lucky enough to get her child into thelocal kindy, says finding somewhere is “acomplete nightmare. For me and all of myfriends with kids, it is just a major issue …We were all on multiple waiting lists.” Otherpeople she knows commute “huge distances”to get their children into a centre.

So why have these shortages arisen?Because, quite simply, there has never beenany control over where centres are set up.Since the childcare revolution began in 2005,centres have been funded wherever they wereestablished, regardless of whether they wouldplug a gap or compete with existing centres.The National government is filling someof the holes, spending $90 million tofund 3,500 childcare places in poor, oftenpredominantly Maori/Pasifika communities.But those projects, while vital, don’t helpparents in wealthier but still optionsstarvedcommunities.

In last year’s election, Labour campaignedon a promise not to fund new centres thatwould compete with existing ones. ClaireJohnstone, a member of the governmentappointedECE Taskforce, which delivered amajor report to the government last year, saysshe can’t see “any reason for the governmentto continue to subsidise centres in areas whereit is simply not needed and it’s becoming acommercial enterprise”.

But regardless of those views, and thetrials faced by many parents, the Ministryof Education sees no need to act. KarinDalgleish, the ministry’s early childhoodeducation manager, says measures such aswaiting lists “can be misleading” as parentsoften put children on several different lists.The ministry “does not have plans” to controlwhere centres are set up, she says.

Nor will it necessarily act on the task force’scall for more centres in so-called communityhubs – existing places like schools, GP clinicsand community centres. Johnstone argues themove would increase the number of centresand allow the government to help familiesbetter: “If you had a hub, where you had earlychildhood education, a medical centre, youthcounselling all in the same area, you wouldstart to see some better outcomes.” Daglieshsays the ministry is still considering the idea,but there are no community hub centrescurrently planned.

Whatever the government does, privateenterprise will provide the answers for someparents. Peter Reynolds, the head of theEarly Childhood Council, says the post-2005surge in new centres has seen waiting listsfall nationwide, even if poorly served pocketsremain. Last year 270 new licences weregranted, he says, and more are on the way.In the southern suburbs alone, the 56-placeIsland Bay Childcare Centre will open on theParade, and a 100-place Little Wonders centrehas just sprung up in the old Athletic Parkcomplex in Berhampore.

Life remains tough, however, especially forthe not-for-profits. Mountford-Gibbs says thekindergartens movement would love to openmore centres, but there’s no money, especiallyafter the government’s funding cuts. In amuch-debated move, ministers decided in 2010to stop funding centres to have all their staffqualify as teachers, instead covering only thecost of having 80% of staff qualified.

Sue Cherrington, an associate deanof education at Victoria University, saysinternational research shows that the qualityof teachers’ interaction with children is thesingle biggest factor in determining thestandard of care. Qualified teachers, she adds,can draw on a wide repertoire of techniquesto deal with different children, rather thanrelying on their own intuition or experience.“You have got a better chance of having highqualityearly childhood education if you have100% qualified teachers.”

The government argued that the movewas needed to contain “spiralling andunsustainable” costs and allows centres toemploy other professionals, such as nursesor Maori and Pasifika experts, who may notbe qualified teachers. It also claimed to begenerously funding early childhood education,pointing out that spending has increased bymore than $1 billion over the last six years.Reynolds, however, says that increase wasneeded simply to keep up with populationgrowth and the rising number of centres.Funding per centre has definitely dropped inrecent years, he says. And there’s no doubtthat the policy change on 100% qualifiedteachers, on top of funding cuts for teachers’professional development, has hit some centreshard. Most have lost $40,000-$50,000 a year,Reynolds says. “That’s essentially one teacher’ssalary that’s walked out the door.”

Mountford-Gibbs says times are so toughthat the Owhiro Bay kindergarten “is aboutto go back to fundraising for toilet paper”.Whereas under Labour it only had to askfor help with major investments, “what’shappened is that with cuts to funding,we have all had our operating allowancescut, so our fundraising now has to go intothose essentials.”

The kindergarten, which charges just $4 anhour for non-subsidised care, is asking parentsfor a voluntary donation of 50c an hour forthe supposedly free 20 hours of subsidisedchildcare. Since the funding cuts took effectlast year, private centres, which typicallycharge $200-300 a week, have raised theirfees, many by around $40 a week.

Some fear fees could rise even more, sincethe ECE Taskforce report last year urgedministers to consider removing the controlsthat prevent centres from charging fees for the20 hours of subsidised care. The report alsoargued that the government should considertargeting funding to the poorest groupsrather than subsidising ECE even for thewealthiest parents.

The government’s response has sent mixedsignals. National’s election manifesto last yearpromised to “maintain 20 hours ECE fundingand the current fee controls for 20 hours ofECE”. But the Ministry of Education has saidit will set up a new funding system by 2015 inresponse to the taskforce’s report.

The funding review will be “approachedcarefully to make sure no families aredisadvantaged”, Dalgleish says. But academicsare already warning of the dangers oftargeting funding too closely. Cherringtonsays the international research shows thatuniversal funding is best for improvingparticipation rates among the poorest families,“because targeting tends to stigmatise familiesand children, who then tend to pull back frombeing involved”.

Rising costs – allied to a shortage ofplaces – also make it hard for mothers to getback into the workforce, despite this being akey part of the twenty-first century welfaresystem. Joanne Aitken says parents forced togo private by a shortage of kindy places canface “horrifically expensive” fees.

“If you are paying exorbitant amounts,” sheadds, “the margins are tight: by the time youdrop them off and you pay whatever you need to for the week, you wouldn’t be getting muchextra on top [from being at work].”

The ECE taskforce also recommended thatparents receive more help choosing an earlychildhood centre, rather than having to relyon social networks. It’s an important point,given the variable standard of care on offer.Johnstone says she saw one centre where“children as young as six months are left tofeed themselves because [staff] don’t have timeto feed them. They are sitting there trying toget a banana into their mouths with limitedmotor skills.” Similarly, submissions to theECE Taskforce raised concerns that “poorquality services operate with little being doneabout them”.

But it’s hard for parents to find out thisinformation beforehand. They can look atEducation Review Office (ERO) reports, butas the taskforce put it, the reports’ languageand style “is not always helpful to parents”.Nor does ERO use any standard measureof performance that would allow parents tocompare centres.

The taskforce said standardised summariesof each centre’s performance should beavailable on a central website to allow easycomparisons. In its election manifesto,National responded by promising parents“more information” about services, thoughwithout giving any details about howperformance would be assessed.

Johnstone says she’d also like to see parentssurveyed about the quality of care theirchildren receive. “If parents were given theopportunity to be surveyed about what theythink on some basic principles and what isbeing offered, that would at least give otherparents a view.”

In response, Dalgleish says ministers willwork with ERO “to establish what informationwill be [made] available and to develop thetools”. She hopes this information will allowparents to choose a service “based on what isimportant to them”.

In the meantime, Cherrington recommendsparents ask about group sizes and teacherchildrenratios, which the international research suggests are key factors – althoughgood teacher-children ratios are less use ifthe teachers aren’t qualified. Other importantpoints are the relationship between teachersand parents, which helps ensure a consistentapproach at home and at the centre, and a“literacy-rich environment” – which can simplymean having plenty of books around, as wellas formal reading programmes.

But Toni Christie, who runs five ChildspaceECE centres in the northern suburbs, saysthere’s no substitute for parents doing handsonresearch – and trusting their feelings.“Parents have to go with their instinct, theirgut feeling,” she says. “It’s a matter of goingin and spending some time in the centre. Ifthey they get a good feeling, those underlyingquality indicators will be in place.”

As long as they can actually get their childinto a centre, that is.

The post Not doing it for the kids appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

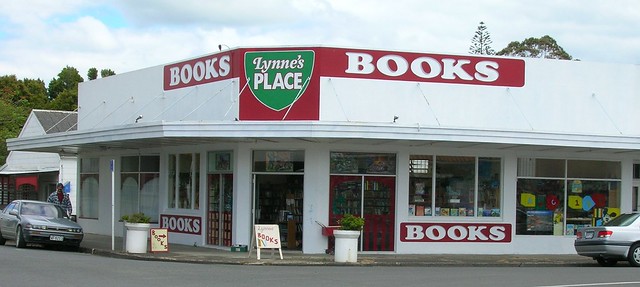

]]>The post Can New Zealand bookstores survive? appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>First it was a trickle, then a flood. A few years ago, sales of e-books – electronic versions of books that can be downloaded and read on a computer or handheld device – were negligible.

Now, Amazon sells more e-books than paper ones, and on some predictions e-books will make up a sixth of a global US$80 billion book market by 2013.

These are glad tidings for online retailers. But might good old-fashioned high-street bookshops, locked into their traditional bricks and mortar, be swept away by this new tide?

Not if the bookshops themselves have anything to do with it. It’s true that they would struggle to sell e-books by themselves, because of the prohibitive cost of applying the complex data protection technology needed to stop e-books being copied repeatedly.

But help is at hand across the Tasman. Australian firm Read Cloud has developed a service that will allow people to buy e-books from independent bookstores and store them online in a “cloud” so that they can be read at any time. Title Page, a site created by Australian publishers, will offer a similar service.

Lincoln Gould, the head of Booksellers New Zealand, says both services should be available soon after Christmas, although progress has been “a bit slower than everybody hoped”.

Discussions are also under way to provide independents with an e-book reader device to sell to customers, as an alternative to products like the Kindle, which can only read Amazon’s e-books. “Once a Kindle is in somebody’s hands, we have lost that customer,” says Tim Blackmore of Nelson store Page and Blackmore.

David Cameron, the owner of Christchurch’s Scorpio Books, says independents “do see” the need to embrace e-books, although the technology will not change his business “as quickly as some of the technology pundits have predicted”.

Although e-books sales here could hit NZ$35 million by 2014, according to an Australian report earlier this year, Gould says “anecdotally, it’s early days”. But this Christmas may see e-book readers like the Kindle become popular presents, “so in 2012 you will start to see the real impact of e-books on the market”.

Cameron hopes to have his website ready to handle e-books early in the new year. But it’s not clear that customers will visit a bookshop’s website when they can buy from an online retailer – and the tide may be turning in the latter’s favour.

Around $100,000 of state money and book licensing fees has been spent making digital copies of existing print titles for the soon-to-launch Great New Zealand E-Books website. But as it stands, site visitors who want to buy the books will be directed either to Japanese-owned online store Kobo, or to New Zealand-based online retailers Wheelers and – technical issues permitting – Fishpond.

What about the bookshops? “That’s the million-dollar question,” says Paula Browning of Copyright Licensing Ltd, which is helping run the project. She is in talks with Booksellers New Zealand, which is thinking about “how that might work”. For his part, Gould says bookshops will be involved, although he is not yet sure of the detail: “A lot of these things are up in the air.”

Scorpio’s David Cameron says it “wouldn’t go down very well” if bookshops missed out on Great New Zealand E-Books sales. But he is much more excited about design innovations – such as textured and 3-D book covers – that turn hardback books into desirable objects, further distinguishing them from their electronic imitators.

And when e-books may be selling at $13 to $14, there is not much margin in it, especially once Read Cloud or Title Page take their cut. Selling e-books is, in Tim Blackmore’s words, mostly about “servicing the local community” that wants to support bookshops. “At the moment,” he says, “we have immensely loyal customers. That may change. It will certainly change if we can’t come up with a solution.”

First published by Fairfax NZ News

The post Can New Zealand bookstores survive? appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post The Vicar of Wall St appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>From the pulpit of his church in Manhattan, the Rev James Herbert Cooper has criticised the worst excesses of the global financial crisis. But can religion really help fix the economy?

Wall Street is the world’s most famous thoroughfare, a street synonymous with great wealth, Gordon Gekko and the adage that greed is good. It is the street that tour guides in San Francisco, perhaps jealous of its splendours, describe as “the most crooked in the world”. It is the street where the global financial crisis originated.

It also has a church. At the top of Wall St, amid the glittering towers of Goldman Sachs and the Bank of New York, sits Trinity Church, founded by Royal Charter in 1697. The rector of the church is the Rev James Herbert Cooper, a 66-year-old New York native who oversees Trinity’s activities as a member of the worldwide Anglican Communion.

Cooper is in New Zealand this week to meet other church leaders from world financial centres, but also to talk about morality and the marketplace.

Tomorrow, in a speech at Victoria University, he will say of those who caused the global financial crisis: “Your sins will come back to haunt you.”

Cooper knows Wall St and its denizens well, having been raised in one of New York’s suburbs, Short Hills, in the 1950s. His father was for more than 40 years the local priest in the Episcopalian Church – America’s version of Anglicanism – “so I grew up in a church family”. At one stage Cooper considered a career as a Chevrolet salesman – “it’s an easier thing to sell than religion” – but the Church won out, although his decision to enter the seminary “came out of the blue, on a personal note”, he says.

“I played baseball at college, and my catcher… was a year ahead of me, a big, brawny guy called Donnie. I said to Donnie one day, `What are you going to do next year?’, and he said, `I’m going to the seminary.’ I thought, wow, really? Hearing he was going to do it really gave me the impetus to think about it seriously.”

Cooper ended up spending the next three decades as a priest in Florida, before moving back to New York to take up the helm at Trinity. Since taking over, he has tried out some radical ideas including, in 2005, a “Clown Eucharist”, in which the service was mimed and parishioners dressed up in big hats and floppy shoes, on the basis that the unpretentious, underdog status of clowns holds a valuable lesson for all believers. The church was packed, he says, although some of his more cynical parishioners wrote him letters saying it was “sacrilegious”.

Cooper likes the city life, even if New York is “kind of a big spot”, and sometimes a dangerous one, too. “I have been shot at a couple of times from family squabbles that I got in the middle of,” he adds, dryly. “You live in a city, stuff happens.”

More pressing than gunshots, however, is the financial crisis. Trinity is in the unusual position of being not just a church but also a substantial landowner. Thanks to a royal land grant three centuries ago, the church owns 3.2ha of prime Manhattan real estate – enough to make Donald Trump jealous, Cooper jokes. Spread over 30 buildings are 200 companies, including big names such as Saatchi & Saatchi, with 15,000 employees.

During the financial crisis, the church displayed “enlightened self-interest”, Cooper says, deferring rents and refusing to sack any of its staff (though it did have to carry out “some difficult programming cuts”). This gave it “a voice to encourage the practice of a high ethic in the financial industry”.

But despite the church’s location, most of Cooper’s parishioners are not Wall St’s titans but its ordinary workers. And that’s the problem when you want to talk about the dangers of unrestrained greed: do the Masters of the Universe actually go to church? “Well, some do,” Cooper says. Most don’t, not on Wall St at any rate.

Nor would they admit to behaving greedily, even if they did. “In my four decades as a priest,” Cooper says, “I have never had someone come to me confessing the sin of greed. Greed is so often disguised and subtle that we don’t even know it’s there.”

In his speech tomorrow, Cooper will suggest that “we might think carefully about possessions… We live fuller lives when we are not possessed by possessions – either what we own, or by the pursuit of what we do not own”. He also suggests asking three questions: what would please God? What would please a generous person? And what pleases yourself? These questions help clarify whether we have let greed “run and ruin our lives”.

Cooper does know personally some of New York’s political and financial decision-makers, including “two or three people who were senior partners in major firms that no longer exist” after the fallout from the financial crisis.

He has had frank discussions with them about what went wrong, although in conversation he comes back to the principle of enlightened self-interest – the idea that profit shouldn’t come at the expense of your clients or customers, because eventually you’ll end up killing the goose that lays the golden egg – rather than going all-out on greed. So how do his friends respond to this line of argument? “[With] the ones who are personal friends, obviously, we’re still friends,” he says, cagily.

One of the problems he faces is that there were plenty of Christians who contributed to the financial crisis. The chief executive of the financial behemoth Goldman Sachs, Lloyd Blankfein, famously said in 2009 that he was “doing God’s work”. And it has long been clear that religion often provides a justification for amassing enormous wealth. This is the “Protestant work ethic”: the idea that in the absence of visible signs of their salvation, the faithful will use material success as clear proof that they have been blessed by God. Very soon the pursuit of that wealth becomes an end in itself.

This points up a contradiction about the United States: although one of the most overtly Christian countries in the western world, and therefore theoretically committed to virtues such as thriftiness, self-denial and equality, it is also the home of some of the world’s greatest personal and financial excesses. (Even Cooper’s own church sports monuments donated by the extravagantly wealthy Astor clan.)

Unsurprisingly, Cooper believes that this hyper-capitalism is a misuse rather than a fundamental consequence of religious beliefs. “People will reach into their quiver and take any arrow they like to achieve what they want. Lots of people use religious rhetoric to get their point – and this [rhetoric] may not be the basic tenet of the religion they are marshalling the forces of.”

This sounds suspiciously like a description of televangelists such as the ludicrously named Creflo Augustus Dollar Jr, whose extravagant lifestyle, complete with two Rolls-Royces and a private jet, pay homage to the power of money. However, the most that Cooper will say of such men, in good Christian fashion, is: “It’s not a theology that I would embrace, though I would embrace the people.”

A fundamental problem, however, with Cooper’s idea of enlightened self-interest – his belief that greed will ultimately undermine a business – is that it doesn’t always hold true. He cites the parable of the prodigal son, who didn’t repent of his wastefulness until he was eating with the pigs; and he claims that “certainly some people have taken a good look at life” after the crisis.

But has anything changed? Bernie Madoff may be in jail, but not one of the chief executives of the firms that caused the financial crisis has been prosecuted. They have, as Cooper will put it in his speech tomorrow, “pull[ed] the rug out from under the worldwide economy”, and got away scot-free.

“There has not been either a self-disciplining within that community or a governmental intervention or review or prosecution,” Cooper admits. Why not? He isn’t sure. But he is struck by the way that businessmen and women, unlike their counterparts in the law and medicine, operate without any explicit ethical code. What does business need, then – a kind of high-finance Hippocratic oath? “That’s a nice idea,” he says, laughing. “Maybe we could convene a few people to think about it!”

Cooper knows, of course, that Trinity Church’s 86m-high Gothic spire was once the tallest point in New York, before it became dwarfed by skyscraper after skyscraper. But he refuses to take this as a sign of dwindling influence. Even if he doesn’t know what the post-crisis economy should look like, he is convinced that religion has a role to play in shaping it.

“Every society has an economy, and spirituality is both a partner and a protagonist in that relationship.” Whether anyone will pay heed to the protagonist is another question.

Was killing Bin Laden ‘justice’?

St Paul’s Chapel, part of the Trinity Church parish, was so close to the World Trade Center bombings on September 11, 2001, that debris from one of the towers knocked down a sycamore in the churchyard. The chapel then became one of the hubs of rescue activity.

So it was no surprise that on May 2, following the killing of Osama bin Laden, Cooper joined former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani at St Paul’s to commemorate those who died in the attack.

But what does Cooper think of the killing, which has made the head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, Rowan Williams, “very uncomfortable”?

“Well, certainly, we at Trinity never celebrate anybody’s death, and we are concerned a little bit about those who do,” Cooper says.

“But there are times when intervention has the potential to stop fighting and save lives.”

He adds: “Some would say there’s justice in that [the killing], given all the deaths in New York.” Does he agree with those people? “I’m on the side of capturing, interrogating, trying and sentencing,” he says.

But, “it’s arrogant and irresponsible to make that statement [that bin Laden should have been captured alive] not knowing the circumstances of that situation”.

Cooper believes the most important next step is reconciliation. To that end, he backs proposals for a Muslim community centre near Ground Zero, which have attracted widespread opposition from right-wing politicians and commentators.

In a statement last year, Trinity Church described those behind the proposals as people who share “common values of compassion and understanding and a commitment to reconciliation and peace”.

Cooper adds: “They are friends, and we support them in what [we hope] they end up doing.”

First published in The Sunday Star-Times

The post The Vicar of Wall St appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post A very civil servant appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>A belief that there shouldn’t be profit in public service has led one former council chief executive to pledge a £100,000 redundancy payout back to the public, but it’s also a break with the past, he says.

Jim McKenna is not, he insists, a saint. He is, in his own words, an “ordinary” guy who likes playing cricket, watching Leeds United and having a drink in the pub afterwards. But he is vowing to do something out of the ordinary.

As the former chief executive of Penwith district council, at the far end of Cornwall, McKenna received a £100,000 redundancy payout when the council was abolished last year. He accepted the money – but has now promised to give it back to local town and parish councils, £5,000 a year over the next 20 years, no conditions attached.

His motives are partly philosophical: “We live in a very poor area, we live in difficult times,” he says, “so I’ve thought about it long and hard and it’s what I want to do. I don’t think it’s appropriate for people who live in high levels of public service to profit from that.”

Redundancy also came during a “horrendous” year for McKenna personally, as he struggled with family and financial problems that resulted in the payout itself being swallowed up. His pledge to give back the money afforded him a clean break with the past, but means he now needs to earn enough to honour his promise. He plans a life in which consultancy work several days a week will earn him enough to pay it back and allow him to work one or two days a week for local charities

Though Cornwall may be popularly thought of as a pretty spot for a holiday, a long stretch of sandy beaches and Rick Stein restaurants, it has its share of social problems. Penwith is one of the 40 most deprived areas in the country, according to 2007 figures, while across the county an influx of second-home buyers is pricing many locals out of the housing market.

One of the charities benefitting from McKenna’s help is the Kerrier and the Fal Credit Union, a mutual savings institution that uses local investments to make small loans to the needy. Based in Redruth, it helps keep people out of the hands of the numerous loan sharks that operate in the area.

“There’s a lot of people who can’t get bank accounts,” says Maria Coleman, the credit union’s secretary. “They come to us – and it’s cheaper for them as well. We don’t put on massive charges like the banks do.”

Further down the peninsula, in Penzance, is Penwith Radio, an internet station that started life as a service for lonely elderly people and now broadcasts a wide range of programmes five days a week.

“It’s a great way of tackling loneliness and isolation,” says Chris Goninan, one of the station’s directors. “This will solve a lot of problems – but it doesn’t take massive amounts of money. It needs will and drive to make it happen.”

To add to that will and drive, McKenna brings a contacts book and an intimate knowledge of local public bodies that will be hugely useful as the station aims for an FM broadcasting licence.

All this is part of his plan to give something back to a community he has come to love after arriving here 11 years ago as a born and bred Northerner (hence his regular 1,000 mile roundtrips to watch Leeds play).

No-one has ever minded his background, he says, because he doesn’t put on “airs and graces”.

Everywhere we visit, he is at ease joking around with co-workers and volunteers – who aren’t afraid to return the favour. We stop by a building site near Redruth, where one of McKenna’s ventures is helping develop mid-priced houses – around the £160,000 mark – many of which he hopes will go to local first-time buyers.

As we inspect the almost completed houses, one worker calls out, jokingly, “Can I have my £5,000?”

These quips aside, McKenna admits opinions are divided on his vow to return the redundancy money: “Some people thought it was a fantastic idea. Some people thought I should have my sanity checked.”

He doesn’t believe in “profiting from public service”, even if his former salary – which local newspaper reports put at £95,000 – set him well above the average.

“Everyone in the district has made a contribution to the redundancy [money], so I should give it back [to them],” he says simply. “I don’t need a lot of money to live. As long as I have enough money to look after my family… and I can afford to watch Leeds, I’m happy.”

When it comes to the wider question of public sector pay and conditions, his views are mixed. High salaries are justified “for the right people if they have the ability to transform services.”

But he admits that in an area such as Cornwall, “I fully understand why people would look at someone earning £95,000 and think, how on earth is that justified?”

Council chief executives moving from one job to another, often picking up handsome payments along the way, can be a problem, he admits.

“I can see why people get vexed if someone walks from one job to another within a matter of weeks. I wouldn’t necessarily regard that as the best use of public money. That may be something the government will look at.”

Either way, he doesn’t regret “for a second” promising to give back the money. “It was one of the best things I’ve ever done… It was a really difficult year, and [the decision] felt good. I very much want to look forward.”

First published in The Guardian

The post A very civil servant appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>The post Public bodies that change family fortunes appeared first on Max Rashbrooke.

]]>A pioneering project in north London shows the value of getting public agencies to work together. But having one person ‘go into bat’ for vulnerable families is just as important.

Angela, a cute one-year-old with tight pigtails, plays placidly amongst the scattered toys in the Packington Estate’s children’s centre in north London. A year ago she was “crying all the time”, her mother, Evelyne, says.

Evelyne, isolated from her family and struggling with her English, had no support: “In the beginning, I didn’t know anybody.”

Help came in the form of the families project run by Hyde, the estate’s housing association. Now in its second year, it brings together 17 public agencies that deal with families, including local schools, health visitors and Islington council.

Vulnerable families on the estate, which is among the most deprived 5% in the country, sit down with representatives from some or all of the agencies to talk about everything they need from public services. A ‘lead professional’ from one of the agencies then works closely with the family, acting as a bridge to other bodies.

For Evelyne, the project has opened up services she didn’t even know existed: a children’s support worker to help her with Angela, a trip to the citizens advice bureau to look at fighting an unfair dismissal from work, and help chasing up a lost tax credit application.